Heart disease describes a number of illnesses which affect the heart and/or the blood vessels in the heart. Heart disease is often thought to affect mainly men (referring to people assigned male sex at birth), as opposed to women (referring to people assigned female sex at birth), but it is the number one cause of death of women in Aotearoa New Zealand, killing more than 55 women every week1.

Heart disease symptoms can be milder and less ‘typical’ in women, so it’s important to know what to look out for. Heart disease can also occur later in life for women, compared to men. This is somewhat due to risks associated with hormonal changes caused by menopause2.

What is heart disease?

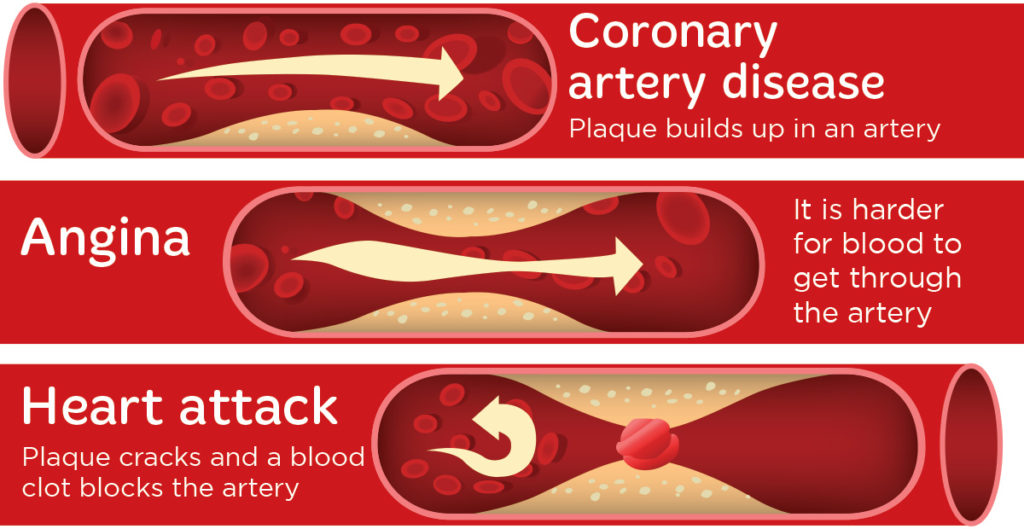

Heart disease describes a group of illnesses that affect the heart and/or the blood vessels in the heart. The most common form of heart disease is coronary artery disease, also known as ischaemic heart disease or atherosclerosis3. Coronary artery disease is a condition where plaque (fatty deposits) build up in the coronary arteries (pipes in the heart). This plaque narrows and hardens in the arteries, which limits blood supply and oxygen to the heart and can cause pain or discomfort, called angina. A heart attack is when the plaque cracks and a blood clot blocks the artery, stopping blood flow to the heart3.

Are the symptoms of heart disease the same?

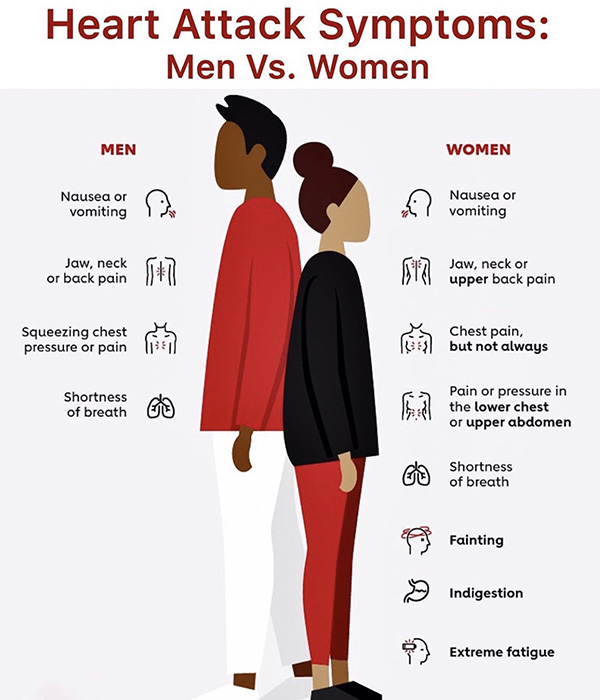

Women can experience any of the heart attack symptoms, but are less likely to seek help as the symptoms may not be as noticeable or severe3.

Chest pain is the most common heart attack symptom, and may feel like pressure, tightness or heaviness in the chest. This discomfort can also be felt in the neck, jaw, shoulder, arms, upper back or abdomen2,3.

Women are more likely to experience symptoms unrelated to chest pain, such as: sweating, shortness of breath, nausea, fatigue, light headedness, and heartburn or indigestion.

No two heart attacks are the same and you don’t need to have all of these symptoms.

If you are experiencing any symptoms of a heart attack, call 111 immediately.

Heart health and gender diverse whānau

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that transgender people have a 40% higher risk of heart disease compared to people who are cis-gender of the same birth sex4. The underlying causes for this increased risk are not yet fully understood, but gender affirming hormone therapy in trans women (for example, oestradiol) can increase the risk of thrombosis (clotting).

We also know that transgender people (whether they take hormones or not), have a higher risk of stroke and heart attacks compared to cis-gender people5, even when other risk factors are adjusted for.

It is now thought that socio-economic factors and stress play a much bigger role in cardiovascular disease development4,5. For example, transgender people can persistently experience discrimination, violence and stigma (both internalised and from others), which can lead to psychological distress and poor mental health. This can make it very hard to make healthy lifestyle choices and increase the likelihood of unhealthy behaviours, such as smoking5.

It is recommended that transgender people should be supported to receive lifesaving gender-affirming care, alongside healthy heart information and regular heart checks, to reduce the risk of heart disease.

Risk factors for heart disease

The risk factors for heart disease are similar for everyone, however the significance of these factors can vary between men and women.

Lifestyle factors » smoking as a young adult has a greater impact on women’s likelihood of developing ischaemic heart disease and nicotine is metabolised faster in women, making it a bigger risk factor3.

Social factors » women are more likely to live in poverty and are more likely to experience depression and anxiety, both of which increase the risk of heart disease3.

Biological factors » diabetes can double your risk of heart disease and women with diabetes have a greater risk of developing heart disease than men1. Biological sex also impacts the way people may experience heart attack symptoms, usually meaning that women and men may present differently.

Pregnancy » health conditions during pregnancy can increase women’s risk of heart disease in later life, for example, gestational diabetes or pre-eclampsia1.

Hormonal and gynaecological factors » people who have polycystic ovary syndrome, have a higher risk of heart disease in the future3. Similarly, women with endometriosis may have a slightly increased risk of having a heart attack or stroke in later life6.

Contraception » some types of hormonal contraception may not be suitable for some people, as they can increase the risk of developing blood clots and may increase your risk of heart disease3. The chance of getting a blood clot is very small and affects up to 1 in 1,000 people using combined hormonal contraception like the pill7. Your GP or Sexual Wellbeing Aotearoa (formerly Family Planning) can help you to choose the right contraception.

Menopause and heart health

Before perimenopause and menopause, high levels of oestrogen help to protect your heart. But as oestrogen levels drop, the risk of heart disease increases3. This change in hormone levels can increase the risk of heart disease due to: an increase in fatty deposits (LDL cholesterol) inside the artery walls, a rise in blood pressure, insulin resistance, carrying weight around the middle, and heart palpitations. Palpitations (or your heart beating faster) are usually harmless, but let your GP know if you are experiencing these symptoms.

Menopausal Hormone Therapy (MHT) is a treatment options for perimenopause and menopause, and works by replacing the oestrogen that your ovaries are no longer making. MHT can help relieve menopause symptoms and helps to provide some protection against heart disease if started in early menopause. MHT is generally safe for most women, however some types of MHT can increase the risk of blood clots and heart disease. Speak with your GP about the best treatment option for you.

Women are more likely than men to experience a heart attack without chest pain, and sometimes heart attack symptoms can be misinterpreted as menopausal symptoms3. This can mean a delay in treatment or being misdiagnosed.

When should I get a heart check?

Everyone should visit their GP for a heart check. Your GP will look at different risk factors for heart disease such as age, ethnicity, cholesterol, blood pressure, family history and other conditions.

Visit your GP for a heart risk assessment based on the following risk factors:

| All women without known risk factors | From 55 years old |

| All women with significant known heart disease risk factors | From 45 years old |

| All Māori, Pacific or South Asian women | From 40 years old |

| All women with type 2 diabetes | As part of the annual diabetic review |

| All women with severe mental illness | From 25 years old |

Note: this table includes people assigned female sex at birth.

People assigned male sex at birth should have a heart check 10 years earlier, as men can develop heart disease earlier than women3. More information here.

Gender diverse whānau can reduce their risk of heart disease by regularly checking hormone levels, and having regular heart checks (depending on blood pressure and cholesterol levels and what treatment they are on)5.

Keeping your heart healthy

In addition to regular heart checks (including blood pressure and cholesterol), you can take action to reduce the risk of heart disease, including exercising regularly, eating healthily, managing stress, and stopping smoking.

Exercise

Sit less and move more. Aim for 30 minutes of movement, 5 days of the week or 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity per week. Moderate intensity means that you feel warmer but can still hold a conversation, for example, a brisk walk, vacuuming or swimming.

Eating healthily

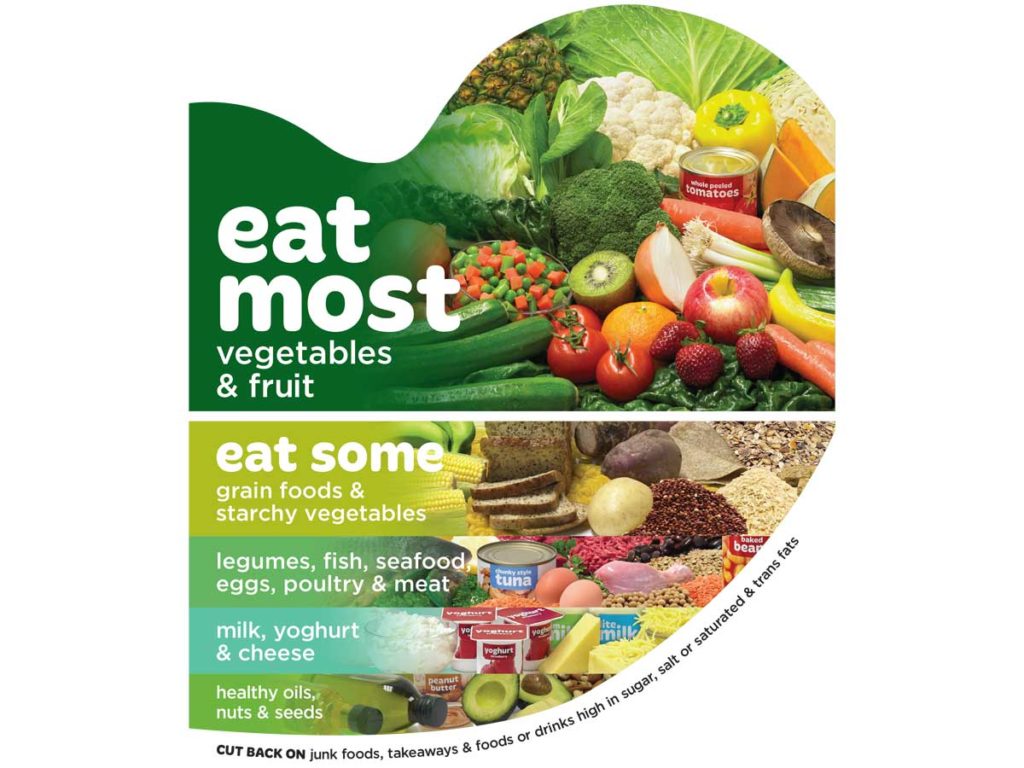

The Mediterranean diet is one of the most studied diets to reduce your risk of heart disease and lower blood pressure and cholesterol. You don’t need to make lots of changes at once, just pick one or two that are achievable, and you can incorporate into your current diet. The Mediterranean diet follows the same principles as a heart healthy diet3,7,8, including:

- Eating more fruits and vegetables, aim for at least five portions daily.

- Choose healthier plant-based oils from nuts, seeds, avocado, olives and healthy oils like extra virgin olive and rapeseed oil (have less palm and coconut oils which are high in saturated fat).

- Eat 15-30 grams of unsalted nuts each day (a small handful) or 30 grams (2 tablespoons) extra virgin olive oil daily. A small handful of nuts most days of the week decreases the risk of heart disease by around 20%.

- Choose less animals fats and opt for reduced-fat dairy products.

- Eat more beans and pulses (e.g. lentils, chickpeas), and less red and processed meats.

- Choose two portions of fish each week, including one oily fish (such as salmon, sardines or mackerel).

- Limit salt and sugar intake.

- Fill up on fibre – choose wholegrain cereals and grains (e.g. brown rice, pasta, wholemeal bread and oats).

- If you drink alcohol, have no more than 10 standard drinks a week for women (see the alcohol page for more information).

Find out more about the Mediterranean diet here.

Managing stress

Mental and emotional wellbeing is important for our health. Feeling stressed for periods of three months or more can start to affect our heart health due to increased blood pressure and blood sugar, caused by higher adrenaline levels3.

Everyone manages stress and anxiety differently – it may help to practice mindfulness or breathing exercises, talk to trusted friends and whānau, or move your body in a way that feels good. Speak to your GP if you feel that your stress is becoming unmanageable.

Stop smoking

Both cigarettes and e-cigarettes (vaping) increase your risk of heart disease3,9. However, e-cigarettes appear to be less harmful than smoking tobacco and can be a useful tool for stopping smoking3.

Commit to quit now with Quitline https://quit.org.nz/ or phone 0800 778 778 for a kōrero.

Useful links

Women and heart disease » NZ Heart Foundation information page about women’s heart health.

Why does menopause increase the risk of heart disease? » NZ Heart Foundation blog about how menopause affects your heart disease risk.

Heart disease in women » Heart Research Institute NZ information page on heart disease in women.

References

- Heart Research Institute New Zealand. Women and Heart Disease, accessed 8 Oct 2024. Available from: https://www.hri.org.nz/health/learn/cardiovascular-disease/women-and-heart-disease

- Healthify He Puna Waiora. Heart Disease in Women, accessed 8 Oct 2024. Available from: https://healthify.nz/health-a-z/h/heart-disease-women/

- Heart Foundation NZ. Your Heart, accessed 8 Oct 2024. Available from: https://www.heartfoundation.org.nz/your-heart

- van Zijverden LM, Wiepjes CM, van Diemen JJK, Thijs A, den Heijer M. Cardiovascular disease in transgender people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Endocrinol. (2024) 190: S13-24. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejendo/lvad170

- British Heart Foundation. Do transgender people have a higher risk of heart problems? Accessed 8 Oct 2024. Available from: https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/heart-matters-magazine/medical/transgender-heart-risk

- Havers-Borgersen E, Hartwell D, Ekelund C, Butt JH, Østergaard L, Christine Holgersson, et al. Endometriosis and long-term cardiovascular risk: a nationwide Danish study. Eur Heart J (2024) ehae563. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae563

- National Health Service (NHS). Side effects and risks of the combined pill, accessed 8 Oct 2024. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/contraception/methods-of-contraception/combined-pill/side-effects

- British Dietetic Association. An update on cardiovascular disease, accessed 8 Oct 2024. Available from: https://www.bda.uk.com/resource/an-update-on-cardiovascular-disease.html

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN 149 – Risk estimation and the prevention of cardiovascular disease (2017), accessed 8 Oct 2024. Available from: https://www.sign.ac.uk/media/1464/qrg149.pdf

- Mohammadi L, Han DD, Xu F, Huang A, Derakhshandeh R, Rao P, et al. Chronic E-cigarette use impairs endothelial function on the physiological and cellular levels. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2022) 42: 1333–50. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.121.317749